Don’t Invent a Plot. Build a World — How Great Historical Fiction Really Begins.

Start from the World, Not the Premise

Many writers begin with a dramatic “what if?” — a plot hook (“What if the printer’s press room broke down on the eve of the Revolution?”) or a character leap (“What if Diderot had been arrested instead of publishing?”). But I recommend the reverse: begin with the world — its pressures, silences, ruptures — and allow your plot to emerge from it.

When you walk this path, the story doesn’t feel imposed; it arises naturally from the lived texture of the time.

What I mean by “the world first”

When I embarked on my new novel titled Encyclopédie, I didn’t at first sketch a hero or an inciting incident. Instead I spent months touring online archives of Paris: old maps, letters to and from Denis Diderot, printer’s records, the collision of Enlightenment ideas and the mechanics of the book trade. I visualised his street, his publisher’s press room, the scent of ink, the whisper of salon gossip. Only after I felt grounded in that milieu did I allow the narrative arc to appear.

Likewise, in my Hemingway novel, Making A Moveable Feast, I delved into 1922 Paris cafés, the river Seine at dusk, the journals and the menus became the terrain before the characters asserted themselves. The characters were shaped by the world rather than the world being shaped to fit an initial plot.

Why this matters

Authenticity of feeling. When you write “world first,” the reader doesn’t just see events—they feel that characters belong in that time and place. The ambient noise, the smells, the social rituals, the unspoken expectations become part of the story’s fabric.

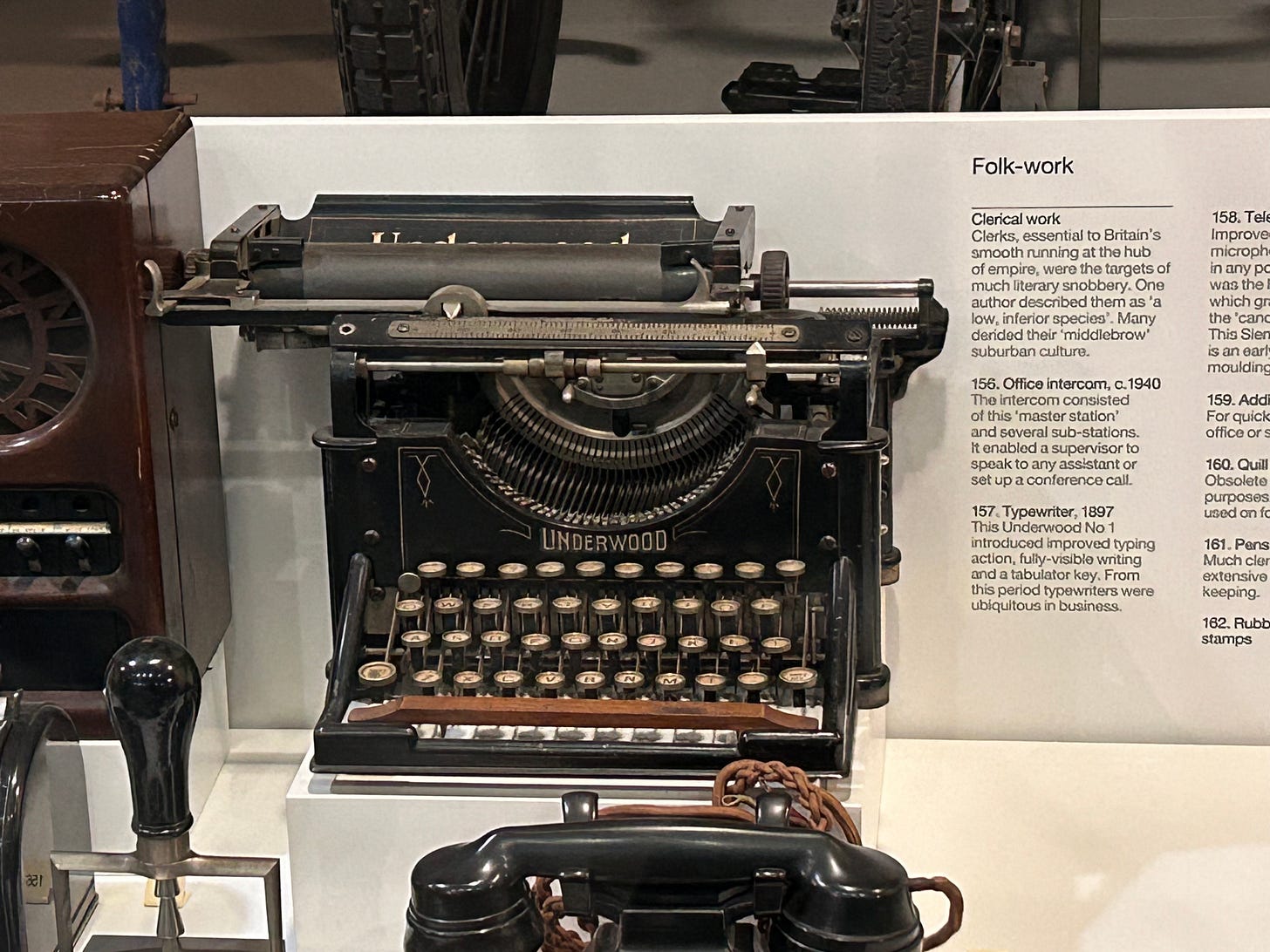

Hidden constraints breed creativity. A world with constraints (printing press limitations, salon rules of conversation, street-politics of Paris) forces the plot to emerge organically: how does the character respond when the ink fails? When gossip overheard in the salon becomes dangerous? When the river floods?

I am writing the story of Denis Diderot and The Encyclopédie and I started to assume he’d get a letter from Voltaire in Potsdam two weeks later. I researched to find the postal service of 1750 was super fast and efficient and might only take three days! I them imagine the hand to hand passes of the letter and the horse rides.

Minimises anachronism. By inhabiting the world first, you reduce the risk of imposing 21st-century values, technologies or conveniences. The story becomes rooted in what was, not what we imagine might have been.

Characters grow out of the setting. The world you build offers the tensions, the silences and the ruptures. Characters don’t just arrive with their own goals—they respond, are shaped by, and in turn shape that world. That makes them more believable, more integral.

A “world-first” practical workflow

Sensory impressions. Write nothing but what the world looks like, sounds like, smells like, tastes like. Collect images, lists of daily life: street-vendors, print workers, café tables, ink-spills, the creak of a wooden door in a Paris maison. The smell of unwashed skin!

Timelines & pressures. Lay out maps of the era: what events loom? What technologies exist (or don’t)? What are the social, political, economic pressures? For example: increased demand for books; censorship threats; salon culture; rising urban migration; the smell of coal in Paris streets.

Lists of daily life. What do the characters (even if unnamed yet) have to deal with? Their breakfast, their route to work, how they send a letter, what they pay for ink, how they queue for the press. These “mundane” moments anchor the world.

Let the characters emerge. Once you feel comfortable inside the world’s constraints and routines, you’ll begin to feel who belongs there, who rebels, who is invisible. The plot begins to sprout from their interaction with the world — rather than you forcing them into a pre-planned dramatic arc.

Write the “world-draft”. Do a “draft” of the setting: write 5,000-10,000 words (or more) of description, daily life, sensory details, no plot yet. Then, mark characters and actions in that draft and allow action to emerge.

Merge world and narrative. Once characters appear, ensure their actions make sense given the world you built. The world shouldn’t just be a backdrop—it must be interactive, in tension with the characters. The plot should feel inevitable in that world.

Quotes

“It’s really important in any historical fiction, I think, to anchor the story in its time. And you do that by weaving in those details, by, believe it or not, by the plumbing.”

Her invocation of “the plumbing” reminds us that the seemingly trivial (how water ran, how ink dried, how letters were sent) grounds a story in its reality.

“Everything in a story is world-building in the same way that everything about us is world-building. … What they wear, what they eat, what they drink, what they value, what they want, this is all world-building and it goes on until the last page of the story.”

Lynch’s remark reminds us that world-building is not just a preliminary task; it permeates the whole narrative. Consider minute details: a press worker’s ink-stained fingernails, a publisher’s ledger scrawl, the ruin of a street-wall. These matters tell you where that story lives.

Writer’s Digest’s composite article “Authors Share Tips on Writing Historical Fiction Novels That Readers Love” (2020 update):

“For historical fiction, the world that our characters populate must believably be one that actually existed in the past, and yet one into which the modern reader enthusiastically enters.”

“When it comes to attitude, read the newspapers of the time… Our sensitivities are not their sensitivities.”

Why this approach fits historical fiction especially well

Historical fiction doesn’t just ask what happened, but what it felt like to be alive in that moment. When you start with a big what-if, you risk flattening the past into a stage for your characters. When you start with the world, you allow the past to hold its weight: the smell of candle-wax in a Paris attic, the way printers argued at dawn, the unremarked infrastructure of cafés and salons, the hidden labour behind a book’s production. Those details give your fiction depth, texture and authenticity.

Caveats and pointers

• Don’t let your world-draft stall the story. Building the world is vital, but the purpose is to enable story. After your world-draft, remember to move onto characters and actions.

• Avoid research-showoff. Just because you know the printer’s press lever works doesn’t mean you dump that explanation on the reader. The world must serve the story. (Lynch warns of “info-dumpy” writing. Yes I can be guilty!)

• Balance the universal and the particular. Readers must feel the world is particular (time, place, machinery of Paris print) but also recognise universal human concerns (ambition, pride, love, fear).

• Allow silence and ripple. Not every moment needs drama. Some of the most powerful writing arises from quieter world-moments (an idle pressman’s hand, a runaway page in the wind) which set up tension, mood or metaphor.

• Beware presentism. The past did not always think like we do. If you start from present moral instincts and only then dress the world around them, you risk anachronism. Your “world-first” method helps you inhabit the mindset of the era.

Summary

When you begin with the world — its smell, its machinery, its routines, its ruptures — the story doesn’t feel like a graft onto history but as though it grew from history. You’ll find your characters emerging more naturally, their arcs shaped by real constraints, the plot becoming inevitable in a way that an imposed “what-if” might not permit.

In short: world first → characters second → plot third.

#HistoricalFiction #WritingTips #AmWriting #WritersOfSubstack #WritersCommunity #PaulWBMarsden #Encyclopédie #MakingAMoveableFeast #CreativeProcess #WorldBuilding #FictionWriting #ResearchToStory #OnWriting #StoryCraft #GreatWriter #WritingAdvice #AuthorsLife

https://open.substack.com/chat/posts/b589accc-39e8-4e4d-97bf-ae52059274ed?utm_source=share

So the GOP was for Bernie, Trump was for Bernie, Putin was for Bernie, The Russians were for Bernie. The far right was for Bernie. The far left was for Bernie,

The Democrats were for Hillary.

Who was Bernie working for? He was working for Bernie, against the Democrats and for, the GOP Trump and the Russians.

https://open.substack.com/chat/posts/b589accc-39e8-4e4d-97bf-ae52059274ed?utm_source=share

So the GOP was for Bernie, Trump was for Bernie, Putin was for Bernie, The Russians were for Bernie. The far right was for Bernie. The far left was for Bernie,

The Democrats were for Hillary.

Who was Bernie working for? He was working for Bernie, against the Democrats and for, the GOP Trump and the Russians.